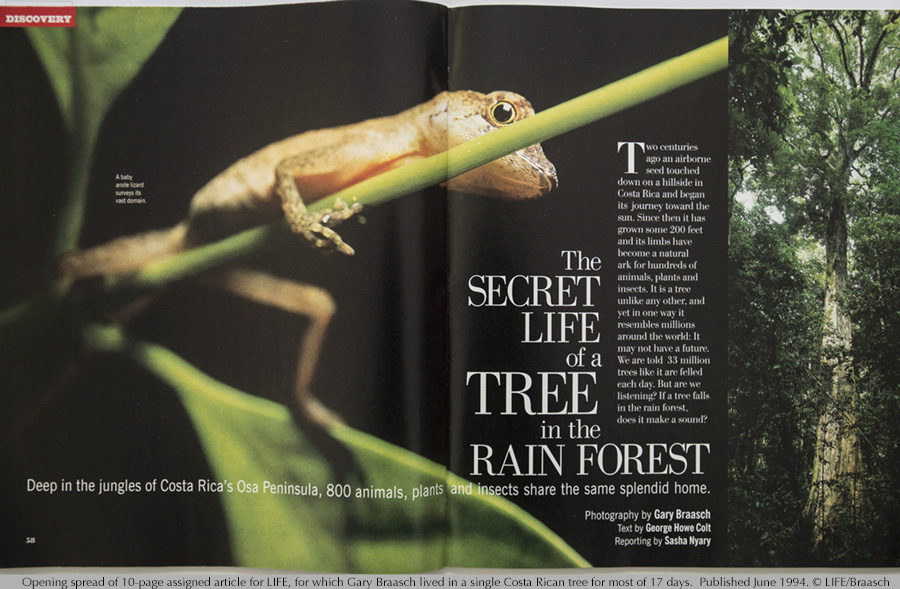

The Secret Life of a Tree in the Rainforest

A three-week assignment from LIFE Magazine to illustrate the richness of the tropical forest. Innovative techniques included support from Costa Rican environmental research center, tree climber to establish platform in 200 foot high tree, and tropical biologist for on-location identification of hundreds of plants, insects and birds. Gary Braasch lived in the tree and under its canopy, most of the time alone, making 4500 exposures on film. Selection of 23 images published in a 10-page feature in June 1994.

My journey to this tropical tree began with a nut of an idea, and sprouted into a photographic record of the rich diversity of a single place, at one moment, as seen by one person.

In the 1980s and 90s biologist Edward O. Wilson, botanist Peter Raven and others reported from research that the tropics are so rich because the micro-climates from mountain to mountain, tree to tree and leaf to leaf are so varied that many species evolve with very limited habitat. This means most species are unknown and easily destroyed by development and exploitation of the rainforest. This and other ecosystem research had strongly influenced my nature photography. However the idea for this job came from LIFE’s science editor, Steve Petranek, who wanted somehow to illustrate the richness of tropical forests. I had already done stories for LIFE about Mt St Helens volcano, Yellowstone National Park and an Appalachian forest, and was called in for a meeting by Picture Editor Bobbi Baker Burrows.

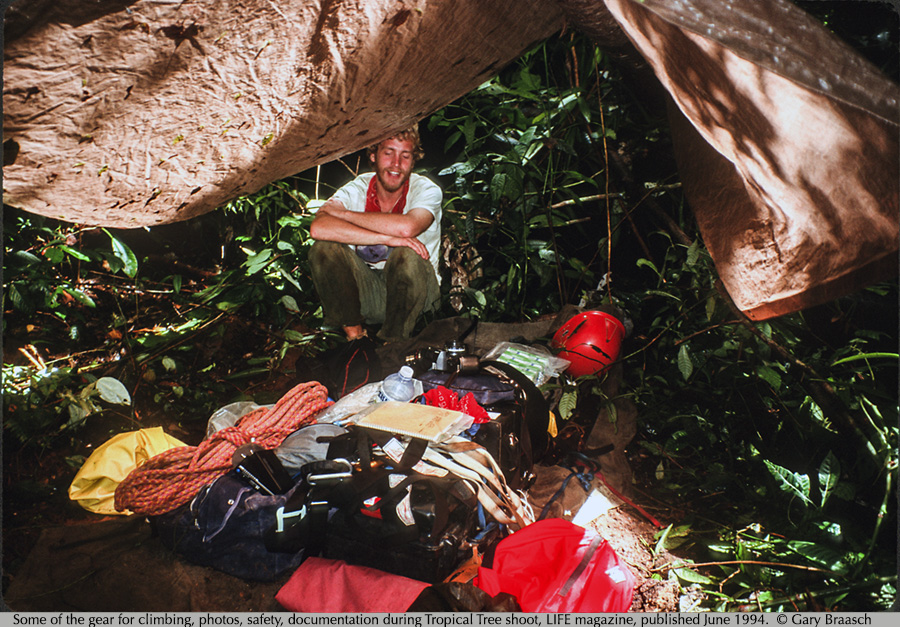

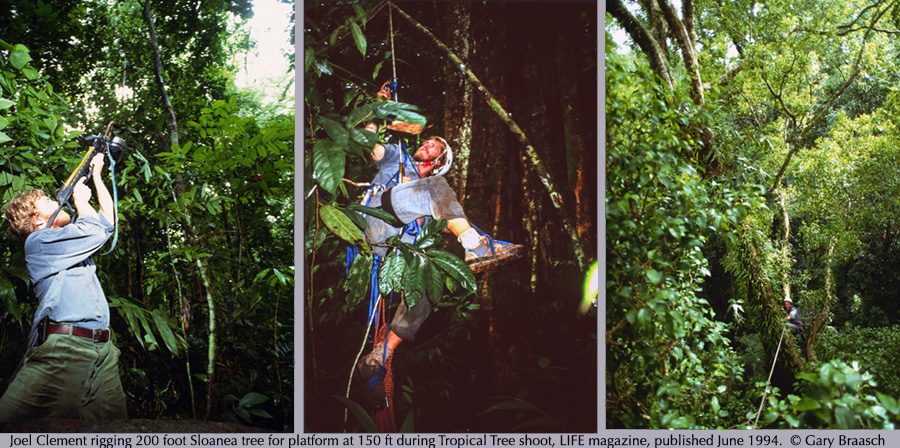

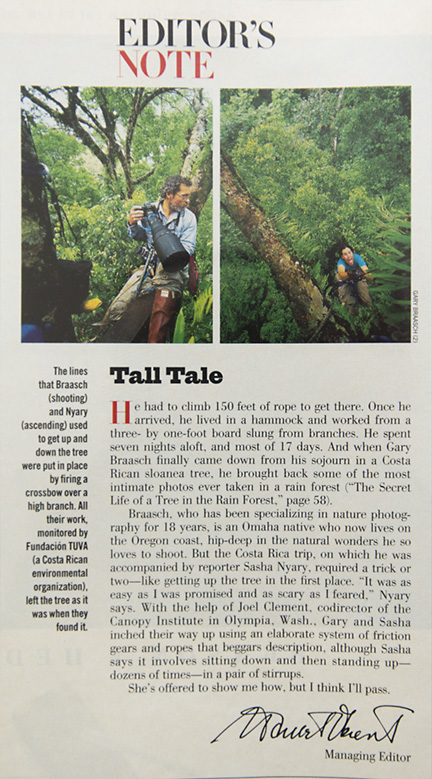

In the story conference, the idea changed from showing a single tropical branch (like in those textbook and museum paintings showing EVERY plant in bloom, every bird, every mammal – impossible to photograph!) to documenting life in a single tree in the rainforest. I still had some doubts, and so did some at LIFE, but I was given three weeks to pull it off at a place and in a way of my choosing. Scientists were starting to actively study the canopy of forests, finding it a complex and very different world from the forest floor, so I knew I wanted to live IN a tree for an extended time, not just around it. I hired a tree climbing biologist, Joel Clement, to work with me, and arranged with the TUVA Foundation in Costa Rica to locate a suitable tree in their wilderness preserve adjoining Corcovado National Park. LIFE gave great support including film, extra cameras, researcher Sasha Nyary and writer George Howe Colt.

I certainly pushed my own envelope of planning, producing, and carrying out a long, complex, and dangerous assignment of my own devising. It was not my first treetop adventure: I had photographed rainforest canopy exploration for the New York Times and old growth forest bird research for Smithsonian. This time would be different, though, because I would be alone in a huge rainforest tree for most of three weeks.

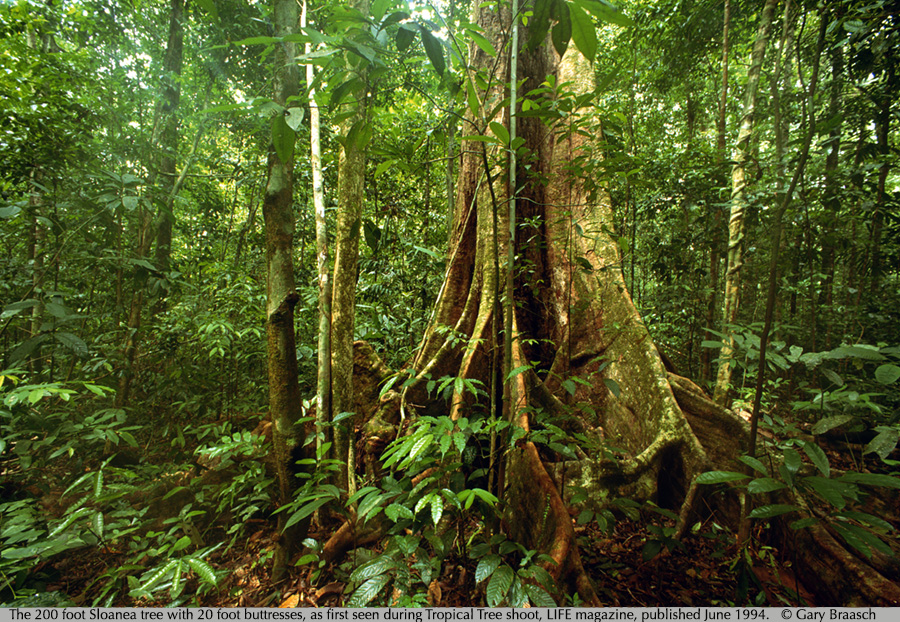

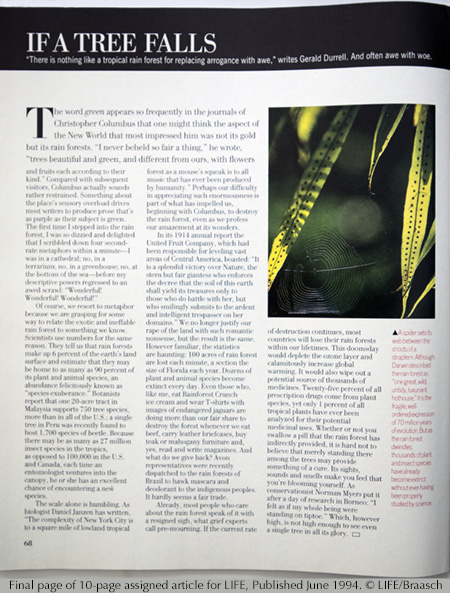

Although there were trees already rigged with platforms at the TUVA station, I ended up searching for an unclimbed tree in a remote part of the preserve. Guided by Miguel Sanches, a local rancher, we explored for several days before finding a magnificent 200 foot golden-barked epiphyte-laden tree with incredible snaking buttresses. We didn’t even know what species it was yet, just that it seemed to epitomize rainforest trees – and had strong branches for climbing.

We brought in our 200 pounds of gear and Joel got busy putting up ropes, shooting guide lines over high branches with a crossbow. Within a day, we were among the branches. Joel installed a simple two-board platform using nylon slings and a rigid hammock for sleeping at the 150 foot level. Then, he went back through the forest. With only brief visits from a hired assistant to bring food and be my safety while climbing up or down the rope, and several days with the researcher from LIFE and a local biologist, it was me alone with the tree and all its life, for the next three weeks..

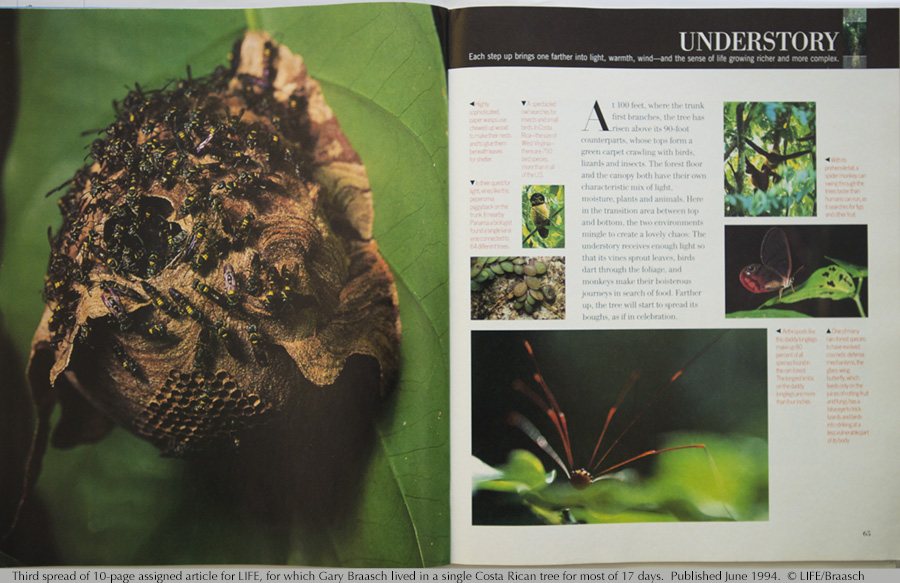

The first time I reached my canopy position alone, it was afternoon, and rich sunset light poured into the rainforest canopy as I moved up the rope. The forest floor had been thick with humidity and nearly dark, but as I left it below I soon caught sight of the sun out over the Pacific Ocean and felt a cooling breeze. My vista opened as I climbed through the thick understory tree branches as if parting a curtain onto the world at the top of the forest.

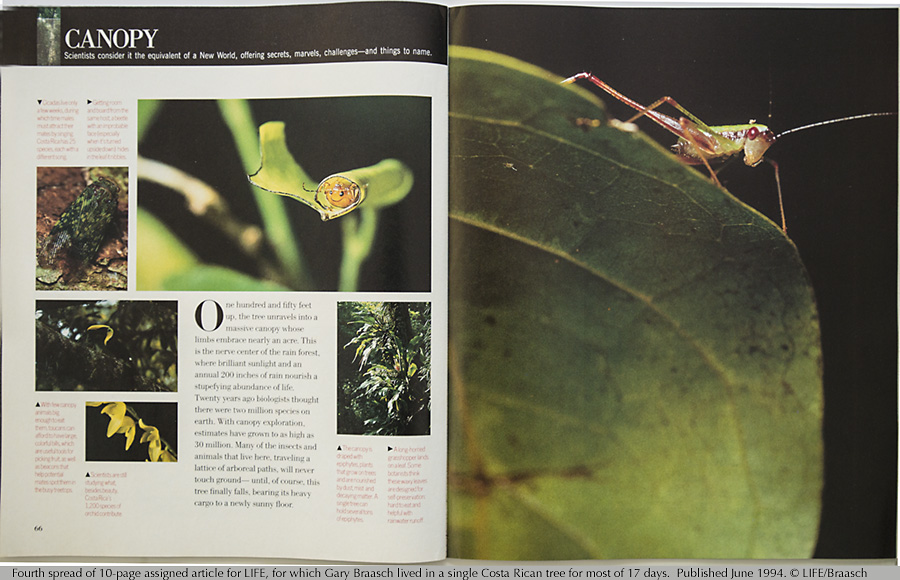

Spider monkeys that I'd only heard from below now were visible in the far branches of the same tree I was in, swinging off toward a neighboring fig tree. The raucous gobbling of macaws and parrots came from every direction as they squabbled over territories and roost sites for the night. In the topmost canopy I could see many tiny birds foraging in the leaves and among the mosses, ferns, orchids, and peperomia that covered nearly every branch. Right in front of my face ants, spiders and tiny insects inhabited the tree's upholstery of epiphytes.

In the last last few meters of the rope climb I, too, became a canopy dweller. The forest floor had disappeared 50 meters below. Hugging a huge branch I swung myself into a crotch from which six limbs reached up to emerge above the rainforest. I sat down on a small board seat installed as part of the rigging, hooked safety webbing to a branch, and fished my cameras out of my backpack. The final sunset rays flashed under gathering clouds. The forest glowed orange for only a moment, then dropped into a blue-green dusk.

A sound like distant truck traffic moaned from somewhere off in the canopy and moved rapidly closer. It must be the wind. No, momentarily I could tell it was rain, a tropical downpour. It was in view now, a gray curtain moving toward me through the canopy. In only seconds I could hear the pock-pock of individual raindrops hitting large tropical leaves as I stashed my gear in waterproof bags and donned a poncho.

The gutteral screams of howler monkeys startled me. They must have been bedding down close but out of my sight, and were apparently just as disturbed by the rain as I was. The deluge was upon us now, and my shoulders stung from the force of the drops. Water was forced through the "waterproof" fabric, and runoff soaked my pants and filled my boots; soon I was totally drenched. Night was coming on, but in the rain I couldn't see beyond my own tree branch anyway. Descending in the wet and dark was foolhardy, and so I remained determined to complete my first night in the rainforest canopy. I thought of my fellow primates and the other canopy animals. Temporarily I was one of them, accepting the weather as part of the rich life of the trees. This is why I'd come, to experience and photograph the rainforest life of a great tree.

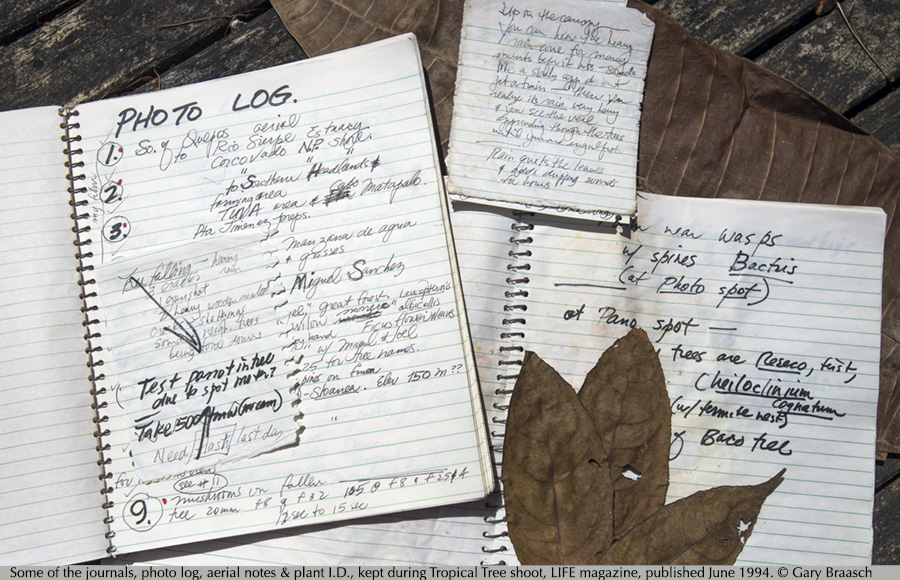

The ground rules of this shoot were that I would photograph anything in and under my great tree. I was at my canopy perch for 17 days, including 7 nights (other nights I hiked out to the TUVA station, returning before dawn; I had one day off). Parts of some days I spent on the ground amid the buttresses and hanging at mid-rope to experience the understory. But living in the rainforest for even three weeks barely parts the curtains on this most diverse and rich of habitats. Many larger animals avoided my tree or just were not in the area. I only had tantalizing glimpses of paca and great black anteater for example, and saw only tracks of resident wild cats. In the canopy, I could not easily move from my perch but had to wait quietly to see what would come into my view. Yet with persistence and concentration I was able to get pictures of nearly everything I saw. And thanks to LIFE researcher Sasha Nyary, our hired biologist and other experts, we were able to identify most of what is in the photographs.

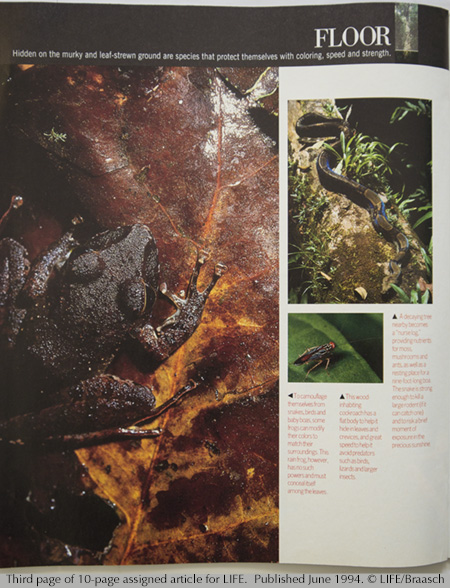

The world of arthropods -- spiders, insects and the like -- reaches its zenith in the tropics, where warmth and moisture are continuous and the number of habitat niches is uncountable. Single topical trees have been shown to be home to more species of insects than live in all of Europe. Naturally in my stay I saw only a tiny portion of the insects that were present, but my photographs are a kind of microcosm: Spiders, cicadas, crickets, flies, shield bugs, leaf hoppers, katydids, millipedes, beetles, cockroaches, butterflies, ants, wasps, dragonflies, long-legged harvesters … 60 species in all.

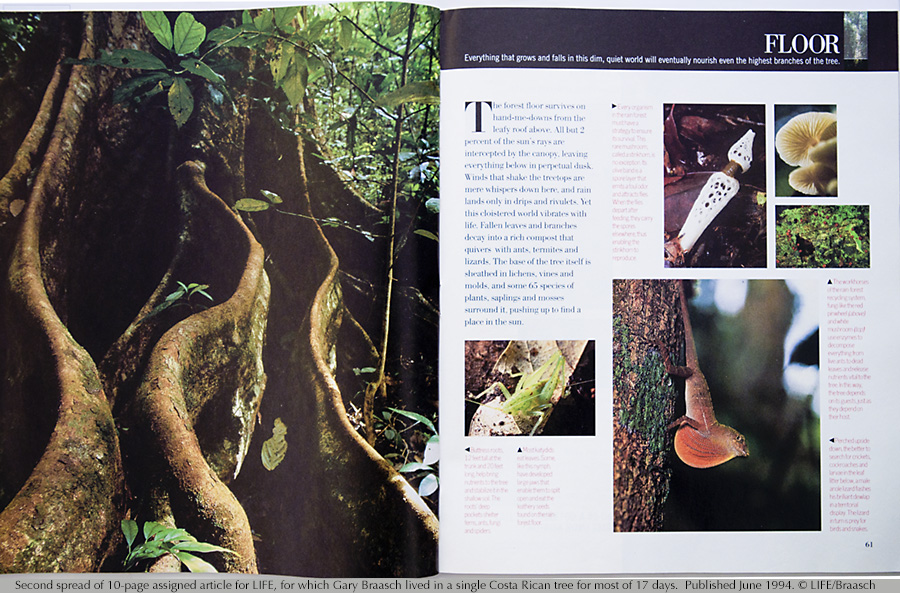

The plant kingdom is even more astoundingly varied and diverse. Vegetation makes up more than 99 percent of tropical biomass. Of course, I was sitting in the largest, most massive plant in my little area, a Sloanea, relative of the linden. Surrounding it was a network of at least 20 understory tree species and large palms. The tree had thick bolsters of epiphytes, plants that live on (but are not parasites of) its branches and bark, including eight orchids, four philodendron species, many ferns and peperomias, and other species. Mosses and lichens were everywhere. On the ground incredible blooms of fungi ranged from common-looking mushrooms to delicate lacy stinkhorns. I observed the same plants repeatedly and saw them grow, bloom, attract pollinators. Between the buttress roots, I found seedlings of my tree.

Photographed in and around the tree were birds ranging from white hawk, spectacled owl, and parrots, to tiny antbirds and other high-canopy flyers; spider and howler monkeys; and reptiles and amphibians including tiny rainfrogs, anoles, fer-de-lance poisonous snakes and one magnificent 3 meter boa. I observed night animals ranging from flashing bioluminescent flies to reclusive kinkajous, but persistent night rains defeated photo attempts.

To capture all this I brought equipment ranging from a panoramic camera to regular 35mm Nikon bodies with 15mm through 500 mm. lenses. During the three weeks I used them all -- sometimes one after another from the same spot. Protected by waterproof cases and river bags containing silica gel, the equipment withstood the moisture and heat very well until, near the end, heavy canopy rain began shorting things out. I had to ship the panoramic home when it began to mold. I shot 125 rolls of Velvia transparency film and edited down to over 2000 prime images.

The memory of this residence in the rainforest canopy is dominated, along with what I saw and photographed, by what I could not record: The smells and sounds of the canopy. At night, especially, the air would alternate between a light fruity odor borne on a breeze through neighboring treetops, and an almost sinister must rising from the tropical earth. In the complete darkness I sat essentially blind, able to sense nearby branches only by star light. My hearing became primary as the sounds changed almost completely from the daytime because the tree was shared by a new set of animals who pursue nocturnal lifestyles. This is one key to the rich diversity of the tropics. Tree frogs sang "teet-teet" at night and the sounds moved as they jumped. I heard owl hootings and a myriad of unidentifiable peeps, dings, cricketings, buzzes, clicks and very spacey whistles. I was startled by sudden wingbeats of a bird or bat right next to me, unseen in the black night. Most nights, though, it rained heavily which made sleeping impossible and created so much noise I could hear very little.

After 22 days at the tree, I personally removed all the equipment, roping the camera bags and boards down to the ground, removing all the slings and carabiners. I hooked my jumars onto the descending climbing rope, and, when I reached the ground, I untied the other end of the rope and pulled it out of the tree. The tree was left as we had found it.

Editors at LIFE were pleased, giving it ten pages – a lot in a wide ranging, ad-filled popular magazine – and the Managing Editor Dan Okrent featured us in the Editor’s Note. His light tone about the production of the shoot is perhaps an indication of the suburban families who made up most of the 1.5 million subscribers. Once again, LIFE had fulfilled its mission of bringing the world in all its wonder and strangeness into people’s homes – a role it played from 1936 until it ceased publication in 2000.